Capsule

- Gelatinous layer surrounding the bacterial cell; gives many bacterial colonies a mucoid appearance.

- Composed of polysaccharide (except in Bacillus anthracis) which varies among bacteria and is used in identification.

- 4 reasons the capsule is important:

- It is a virulence factor; inhibits phagocytosis.

- Antibodies vs. capsular polysaccharides used to identify bacteria.

- Quellung reaction used in clinical labs—when homologous antibody present, capsule swells.

- Capsular polysaccharides elicit protective antibodies as antigens in certain vaccines; Ex. Capsular polysaccharides from 23 types of Streptococcus pneumoniae are in the current vaccine.

- It may play a role in bacterial adherence to human tissues and in formation of biofilms.

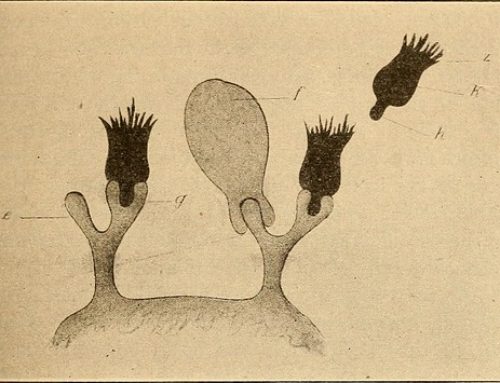

Flagella

- Long, filamentous appendages that propel bacteria towards nutrients and other attractants (chemotaxis).

- Composed of multiple copies of a single protein, flagellin organized in intertwined chains.

- Proton motive force provided by ATP provides energy for movement.

- Present in characteristic numbers (1 or many) and arrangements (at the end or all over the bacterial surface).

- Most common in rods, not cocci.

- May play a role in pathogenesis; Ex. coli and Proteus vulgaris are common causes of urinary tract infections (UTIs), perhaps because their flagella move them up the urethra into the bladder.

- Antibodies vs. flagellar proteins are used to identify some bacterial species; Ex. Salmonella

Pili (Fimbriae)

- Hair-like filaments extending from cell surface.

- Shorter, straighter than flagella.

- Composed of the protein, pilin, organized in helical strands.

- Found mainly on Gram-negative organisms.

- Mediate attachment of bacteria to specific receptors on human cells; can be considered a virulence factor.

- Sex pili function during conjugation.

Glycocalyx (slime layer)

- Polysaccharide coating secreted by many bacteria that mediates adherence to skin, heart valves, catheters, etc. even teeth (basis of plaque and cavity formation); i.e. formation of biofilms. Similar to a capsule, but more loosely constructed.

Spores

- Highly resistant structures formed intracellularly by certain bacteria (Gram-positive bacilli: Bacillus and Clostridium) when nutrients are scarce.

- Composed of bacterial DNA, small amount of cytoplasm, cell membrane, peptidoglycan, a little water, and a thick, keratin-like coat.

- The outer coat provides remarkable resistance to heat, dehydration, radiation and chemicals; likely due to dipicolonic acid, a calcium ion chelator found only in spores.

- Have no metabolic activity and can remain dormant for years.

- When water and nutrients become available, spore may germinate and give rise to a single bacterial cell.

- Important features of spores and their medical implications

| Important Features of | Medical Implications |

| Highly resistant to heating: are not killed by boiling (1000C), but are killed at 1210C. | Medical supplies must be heated to 1210C for at least 15 minutes to be sterilized. |

| Highly resistant to many chemicals, including most disinfectants. | Must use “sporicidal” solutions to kill spores. |

| Can survive for many years, especially in soil. | Wounds contaminated with soil can get infected with spores and cause diseases such as tetanus and gas gangrene (caused by Clostridium species). |

| Metabolically inactive. | Antibiotics are ineffective against spores; plus they cannot penetrate coat. |

| Formed when nutrients are limited, but germinate when nutrients become available. | Usually see bacteria, not spores, in specimens from wounds (why?). |

| Produced by members of only 2 medically important genera, Bacillus and Clostridium (Gram-positive rods). | Infections resulting from spores can be attributed to either Bacillus or Clostridium species. |

Photo by adonofrio (Biology101.org)

Leave a Reply