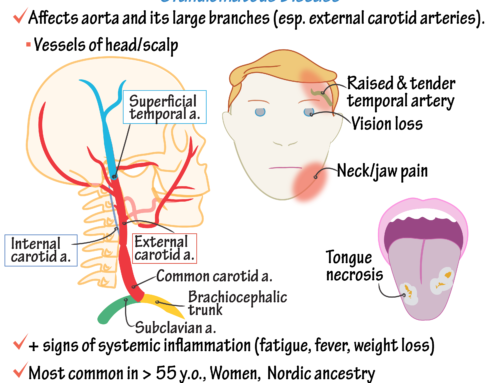

Definition: Granulomatous vasculitis of large arteries.

Patient population: Mainly young women. F >> M 8:1, 90% age < 30

Symptoms: stroke, asymmetric blood pressures, pain

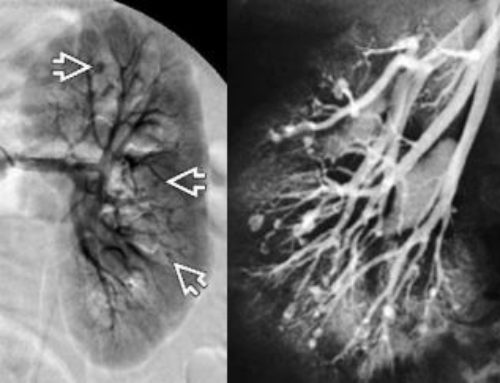

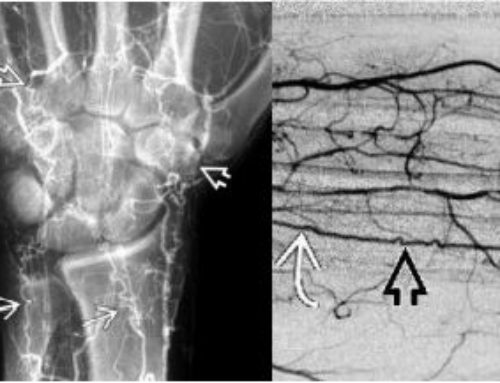

Digital subtraction angiographic findings: Stenosis of the aorta | Great arteries | Pulmonary artery

- Type I = arch + arch branches

- Type II = descending aorta + abdominal branches

- Type III = arch + abdominal aorta

- Type IV = PA + aorta

Treatment: steroids are the mainstay. Angioplasty can be performed, but not during active phase. Sedimentation Rate which is an indicator of active inflammation should be normal before attempting angioplasty.

Takayasu arteritis, also known as Takayasu’s disease or Takayasu’s syndrome, is a rare autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation of the aorta and its major branches. The aorta is the largest artery in the body, carrying oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body.

Symptoms of Takayasu arteritis typically appear in young women, most commonly between the ages of 20 and 40. The disease can cause a range of symptoms, including fatigue, weight loss, fever, and joint pain. In some cases, Takayasu arteritis can lead to the development of aneurysms, or bulges, in the aorta or its major branches.

The cause of Takayasu arteritis is not fully understood, but it is thought to be an autoimmune disorder, in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. This leads to inflammation of the aorta and its major branches, which can cause the blood vessels to narrow or even become completely blocked.

Diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis is typically made based on a combination of clinical symptoms, imaging tests such as CT scans or MRIs, and blood tests. Treatment for the disease typically involves the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive medications to control inflammation and prevent further damage to the blood vessels.

While there is no cure for Takayasu arteritis, early diagnosis and treatment can help prevent serious complications, such as aneurysm formation or complete obstruction of the blood vessels. It is important for individuals who are at risk for Takayasu arteritis to be monitored by a healthcare provider and receive regular check-ups to ensure the disease is properly managed.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

●Takayasu’s arteritis is an uncommon chronic vasculitis of unknown etiology, which primarily affects the aorta and its primary branches. Women are affected in 80 to 90 percent of cases, with an age of onset that is usually between 10 and 40 years. It has a worldwide distribution, with the greatest prevalence in Asia.

●The pathogenesis of Takayasu’s arteritis is poorly understood. The inflammation may be localized to a portion of the thoracic or abdominal aorta and branches, or may involve the entire vessel. Although there is considerable variability in disease expression, the initial vascular lesions frequently occur in the left middle or proximal subclavian artery. As the disease progresses, the left common carotid, vertebral, brachiocephalic, right middle or proximal subclavian artery, right carotid, vertebral arteries, and aorta may also be affected. The abdominal aorta and pulmonary arteries are involved in approximately 50 percent of patients. The inflammatory process within the vessel can lead to narrowing, occlusion, or dilation of involved portions of the arteries in which causes a wide variety of symptoms.

●The onset of symptoms in Takayasu’s arteritis tends to be subacute, which often leads to a delay in diagnosis that can range from months to years, during which time vascular disease may start and progress. It is not uncommon for the consequences of the arterial disease to be the first sign of TAK noticed at presentation. As progression of narrowing, occlusion, or dilation of arteries occurs, there is resulting pain in arms or legs (limb claudication) and/or cyanosis, lightheadedness or other symptoms of reduced blood flow, arterial pain and tenderness, or nonspecific constitutional symptoms.

●The physical examination of a patients with Takayasu’s arteritis should particularly focus on accurate measurements of blood pressure, palpation of pulses, identification of bruits, and careful cardiac auscultation.

●The diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis should be suspected in a patient who has constitutional symptoms, hypertension, diminished or absent pulses, and/or arterial bruits. In most cases, the diagnosis is based upon suggestive clinical features and specific imaging findings of the aorta and/or its branches. Additionally, Takayasu’s arteritis or other forms of large-vessel vasculitis must be considered either in patients incidentally found to have findings suspicious for vasculitis on imaging obtained for other clinical indications or when vasculitis is found on histologic examination of surgically removed segments of arteries.

●There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for Takayasu’s arteritis. Testing for acute phase reactants such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) may provide additional support for the presence of a systemic inflammatory process; however, normal values of ESR or CRP should not markedly deter making the diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis.

●Imaging studies are essential for establishing the diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis and for determining the extent of vascular involvement. Patients with suspected Takayasu’s arteritis should undergo imaging of the arterial tree by magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA) to evaluate the arterial lumen. In general, we favor using MRA to evaluate for TAK, since it avoids the radiation exposure and risks of iodinated contrast of CTA; similarly, if periodic repeat studies are anticipated, MRA is again the preferred choice. Imaging of the arterial tree of the chest, abdomen, head and neck, or other areas by MRA or CTA demonstrates smoothly tapered luminal narrowing or occlusion that is sometimes accompanied by thickening of the wall of the vessel

●Conditions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis include giant cell (temporal) arteritis (GCA), IgG4-related disease, Behçet syndrome, infectious aortitis, fibromuscular dysplasia, atherosclerosis, genetic causes of aneurysms such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and other diseases which can feature large-vessel vasculitis/aortitis such as Cogan’s syndrome, relapsing polychondritis, and spondyloarthropathies.

Leave a Reply