Intimal Hyperplasia

This is the common pathway following vascular injury (traumatic, iatrogenic, angioplasty, stent, etc.).

After PTCA, this process usually occurs for 8-12 weeks and then stabilizes.

Some patients are intima formers, leading to intimal hyperplasia – re-stenosis or in-stent stenosis.

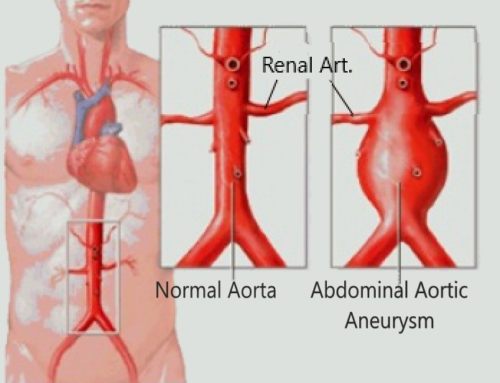

ORIGIN: 85% heart (afib, post MI), 10% aneurysms (aorta > iliac > subclavian)

FINDINGS: abrupt occlusion (pop, renal, SMA, etc) with a meniscus and no collaterals

Atheroembolism

Small microemboli, usually angiographically occult

This is the cause of “Blue Toe Syndrome”

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

●Atheroembolism, also known as cholesterol crystal embolism or cholesterol embolism, refers to arterio-arterial embolism of cholesterol crystals or small pieces of atheromatous material originating from an atherosclerotic plaque usually from the aorta but occasionally from other arteries. Cholesterol crystal embolism results in partial or total occlusion of small arteries, leading to tissue or organ ischemia.

●Risk factors for atheroembolism include patient factors such as hypertension, advancing age, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and diabetes. Anatomic factors associated with the aortic atherosclerotic plaque, such as plaque thickness ≥4 mm, plaque ulceration, or the presence of mobile debris, increase the risk for embolization.

●The clinical diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism should be suspected in patients with known atherosclerotic disease and the development of renal failure; transient ischemic attack; cerebral infarction; signs of intestinal ischemia; digital ischemia; typical skin findings or Hollenhorst plaques in the retina, particularly following arteriography; cardiac catheterization; vascular surgery; or trauma to the abdomen. The diagnosis is more difficult in patients who do not have these features, particularly if cholesterol crystal embolism has occurred spontaneously.

●The presence of complex aortic plaque on imaging studies supports the diagnosis. Atherosclerotic plaques can also be seen using transthoracic echocardiography, abdominal ultrasound, and endoscopic ultrasound of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

●Laboratory testing is generally nonspecific but may indicate the effects of end-organ ischemia. A definitive diagnosis depends upon pathologic specimens. Biopsy should be performed whenever the diagnosis is in doubt and when the specimen can safely be obtained from the patient; debrided or amputated tissue and thrombectomy specimens should be sent for pathologic examination since these represent no risk to the patient. The histologic hallmark of cholesterol crystal embolism is the presence of “ghosts” of cholesterol crystals or cholesterol clefts within arterioles.

●The treatment of cholesterol crystal embolism is primarily medical, consisting of risk factor reduction. Statin therapy is indicated as part of risk factor reduction and appears to reduce the rate of recurrent embolism.

●Surgical or endovascular treatment may be indicated if a clear embolic source is identified, the source is anatomically suitable, and the patient is an appropriate candidate for surgery. For patients who meet these criteria, we suggest surgical or endovascular treatment to remove or exclude the embolic source

●We suggest not routinely anticoagulating patients who are diagnosed with cholesterol crystal embolism. Anticoagulation with heparin, warfarin, and use of thrombolytic therapy are all associated with the development of cholesterol embolism, although a causal relationship has never been demonstrated. However, patients with another indication for anticoagulation, such as thromboembolism or deep vein thrombosis, should be treated.

●The prognosis in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism correlates with the degree of the underlying atherosclerosis and is overall poor.

Leave a Reply